Halfway Through, and a Book Writing Q&A

On changing publishers and what it's like to write a book

NO AI TRAINING: Without in any way limiting the author’s [and publisher’s] exclusive rights under copyright, any use of this publication to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

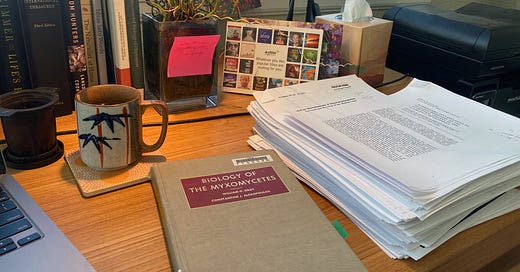

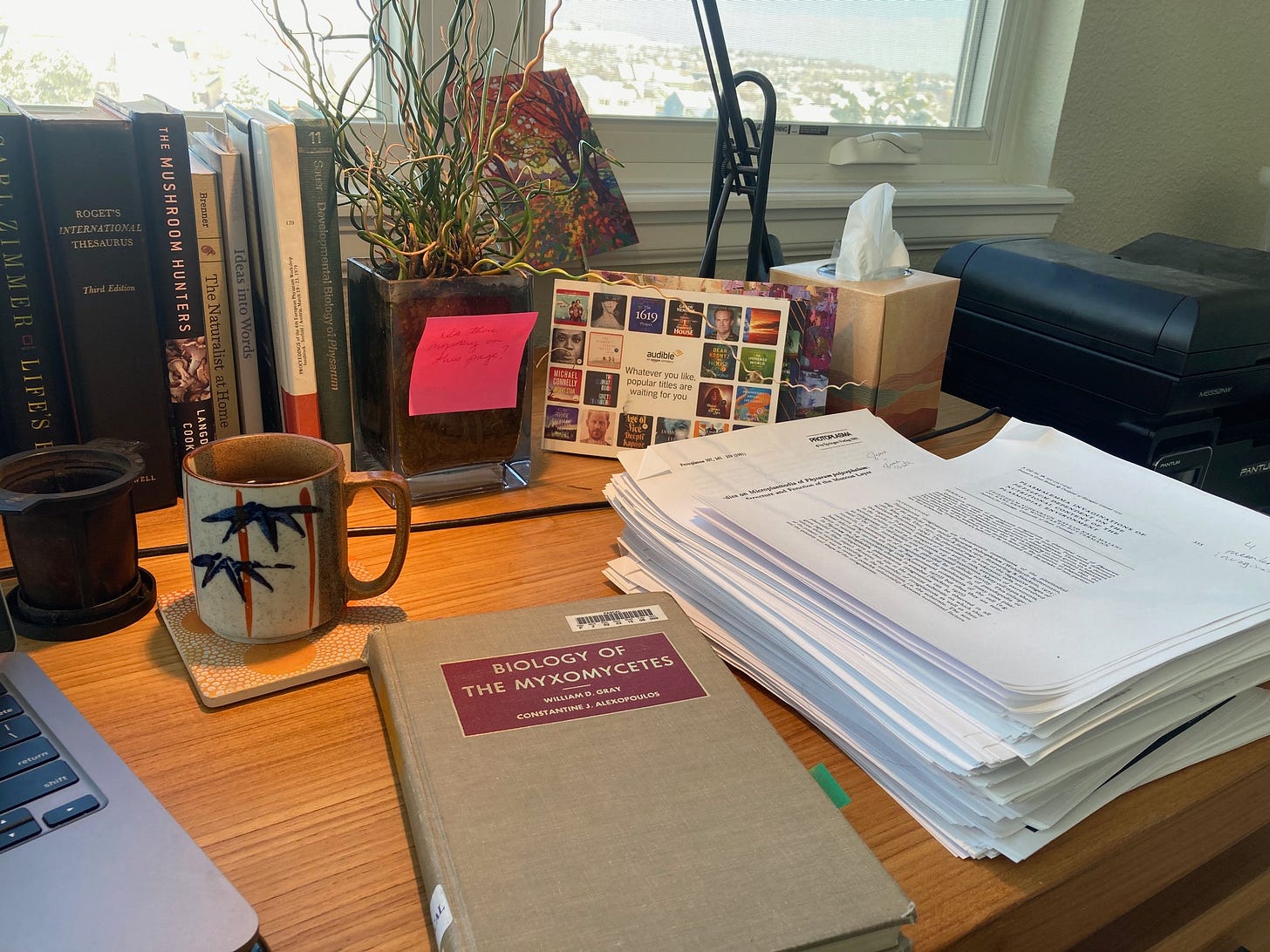

I’m finally approaching halfway through writing The Slime Mold’s Guide to World Domination and I have news: my book has changed publishers. Last year, my acquiring editor moved from Penguin Random House to Simon & Schuster, and requested my book follow. I agreed, and after four months(!) of waiting and contract renegotiations, I signed on the new dotted line last month.

Since the publishing industry seems to be in perpetual upheaval, books apparently get “orphaned” a lot as editors migrate. This is not generally considered to be a good thing from the author’s perspective, unfortunately. However, I was lucky to both have another enthusiastic editor at PRH volunteer to adopt my book (rather than getting assigned to it, which often results in a less-than-ideal dynamic) but then also to have the original acquiring editor believe in my book so much that it was worth the effort to try to resell it to new bosses, which he did. I am grateful to both editors for their faith and enthusiasm in my work.

Today I thought I’d do a little Q & A about science book writing, since this process is so mysterious, and you may be wondering what I’ve been up to the last year.

Q: How hard was it to get an agent and sell your book?

A: It was difficult, but not as hard as it is for fiction authors. I learned the hard way that you should not approach one agent at a time – given the freedom to take their time, they usually will. If you get a yes from one agent, that speeds up the decision-making process for the others, so I recommend aspiring authors query about three to five agents at a time. Before you approach the next batch (if necessary), recalibrate your material based on any feedback you got.

My process took about five months from my first submission to getting a yes and I ended up approaching five agents during that time. Two were decisive nos. Two were almost yesses. One was an enthusiastic yes. The yes was the fourth answer out of the five. My understanding is that it is not uncommon for fiction authors to have to submit to 80 or 90 agents before getting their first yes, so comparatively speaking, we have it easy.

But believe me, no amount of rejection is fun, and there were nights after I got rejected that I cried and questioned whether I even had a future in this business — and who was I if I wasn’t a science writer? Consequently, I was already training to be a native plant landscaper if the whole book thing didn’t work out.

As for the book sale itself, that went quickly. We submitted to three editors and had strong interest within two days. The book ended up going to auction and there were two bids. And just like that, after decades of dreaming about it, I had a real book contract!

Q: How much preparation did you do before approaching agents?

A: The idea of writing the proposal was very intimidating to me. I worried I’d write one and then if I did get an agent they’d make me toss it out and write a new one to their specifications. It kept me from writing the book for many years. The consigliere of my book (a mafia term I am here using to mean my chief strategist) recommended I just start writing the book, which seemed much less intimidating. Since I already had years of experience and a platform as a science writer, he counseled that once I had significant book and was far enough along to believe I could finish it, taking care of the rest wouldn’t be too hard. And he was right.

I started writing the book around 2016, just fifteen minutes a day (that process is a whole other story), and then spent January - May of 2022 (right after I nearly lost the whole book in the Marshall Fire) doing nothing but working on it. So when I approached agents, I went with a polished query letter and two full book chapters. None of them complained I didn’t yet have a proposal. Once I had my agent, I wrote the proposal in a couple of weeks (how much easier it seemed once I had wind in my sails!), and we worked together to polish that and the sample chapters over the next month.

Q: What is it like writing a book?

A: This has been, without question, the most satisfying professional experience of my life. I actually look forward to starting work in the morning, and I’m bummed when I have to quit. The time flies by (this is actually a double-edged sword because in the long term it actually makes life feel measurably shorter!). I cannot believe how much fun I am having. How many people can say that about their jobs?

On the other hand, by pure chance, in the last year I’ve had the most health challenges that I’ve faced in any single year of my life. None of them turned out to be life threatening or shortening, thank god, but several were quite debilitating -- between all the tests, doctors’ visits, and just feeling lousy -- and made it hard to work.

Long ago, I thought I wanted to be a bench scientist, and I got depressed when I realized it wasn’t for me. That was especially confusing because I still loved science. What I have learned writing this book is that I actually WAS meant to do science research – science book research. The process of writing this book has to me been like getting to be a detective and prospector combined – digging through old books and journal articles trying to solve a science mystery, uncovering both gold nuggets and whole Comstock Lodes of amazing and interesting forgotten science in the process.

It can be exhilarating. I have so many times gotten to have light bulb moments where I say – ahh! I finally understand this piece of the mystery now. Or – THAT’s how they figured that out. Or, oh my god, can you believe THIS thing they found out that slime molds can do that no one knows about! And these answers can turn up in totally surprising and unpredictable places, which is also a big part of the fun.

Then I make get to make it all into an entertaining story, which is the easy part. Not once have I had writer’s block. On the contrary, my Achilles’ heel is that I am a slow reader, and careful reading of often difficult texts is almost always the first step of science book writing. And let’s be honest: there are unpleasant parts too. No job is perpetually fun. Even with otter.ai, I still have to go in and manually fix the interview transcripts. Sometimes, the right turn of phrase just won’t come. But overall, I’m in heaven.

Robert Caro, the revered author of The Years of Lyndon Johnson and The Power Broker, said he wanted to become an author because years ago, that was something people aspired to be, like a firefighter, or an astronaut. You don’t really hear people say that anymore. Here’s what I think you should know: becoming a nonfiction author can be a dream job, and not nearly as difficult as breaking into the world of fiction books if you are already a professional writer or journalist. If you are at a crossroads in your writing career, give it some serious thought.

Next time, I’ll answer some more questions about getting started writing science and nonfiction books.

Any questions on this week’s edition? Ask away!

I am very much looking forward to your book, and I am happy to read about your progress and success in changing publishers. I am an academic and a science fiction scholar. In one of my academic books, in addition to discussing a number of science fiction novels and short stories, I had a chapter about slime molds in which I approached scientific papers about slime mold intelligence as if they constituted a science fiction narrative, because the actual behavior of Physarum polycephalum struck me as being as bizarre, and yet as illuminating about questions of life and meaning, as any of the science fiction texts I was also writing about. -- Steven Shaviro