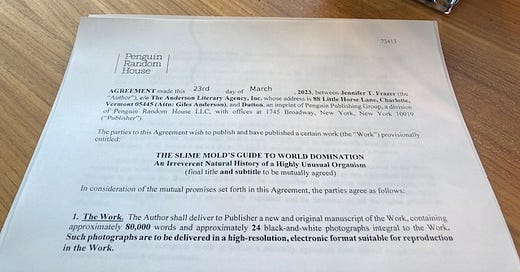

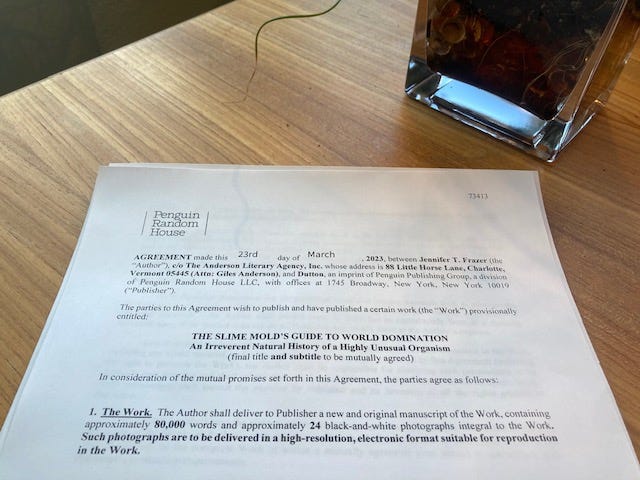

The Slime Mold's Guide to World Domination

I will be the author of an Actual Book, coming to you in 2025

NO AI TRAINING: Without in any way limiting the author’s [and publisher’s] exclusive rights under copyright, any use of this publication to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

I am overjoyed to announce that I have signed a book contract with a division of Penguin Random House called Dutton, and am actively working on my first book.

I am attempting to write a funny natural history of slime molds that’s also a mystery — how can a single cell possibly be intilligent? — with a plot twist ending. Send your book-completion brain rays my way, please.

As a first-time book author, I have often wondered what the process of writing a book is really like. So I’m going to share parts of my experience so far with you, names redacted to protect the innocent (that would be everyone but me).

I first had the idea to write this book about 10 years ago. Actually, I had the idea to write a book waaaaaaaaaay back in grad school at Cornell University (when trilobites roamed the Earth), where I was studying plant pathology. I was in grad school more or less as a stalling tactic: I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life and I needed some more time to figure it out. I chose plant pathology because I had been very interested in biodiversity since high school, and I figured plant pathology would give me the maximum number of weird little things to study. All kinds of things attack plants!

I was not disappointed with my choice. I remember walking through the silent and dusty stacks at the library one day and thinking “My mission in life is to tell the world about all the magical creatures buried in these stuffy journals.” At the time, I thought that meant writing a book about biodiversity generally.

Then I went to grad school at MIT to study science writing, and I learned about the importance of storytelling to grabbing readers. Particular stories. Of particular things. Five or 10 years later, somehow the idea of that general book on biodiversity had settled down to a book about one organism: the slime mold. There is more to the choice of that particular creature, but I will save that for a future date.

Around that time I won the AAAS Science Jounalism Award for a story I did about the investigation into a rash of mysterious elk deaths while I was the health and science reporter at a newspaper in Wyoming. When I went back to MIT to claim the award, I mentioned my book idea and how overwhelming the idea of actually doing it while holding down a day job seemed to the director of the science writing program. I didn’t know where to start. He said, “Have you considered starting a blog instead?” That put me on the path to Scientific American, where I blogged for nine years.

Shortly after my blog was picked up by SA in 2011, I mentioned my slime mold book idea to a fellow MIT alum at the NASW meeting. She mentioned she had just gotten an agent and sold a proposal, and offered to introduce me. I jumped at that opportunity. The agent was kind and smart, but after a while I got the feeling she was pushing me to write a book that was not the book I really wanted to write. Instinctively, I backed away, still also haunted by the feeling that I was inadequate to the task and didn’t really know what I was doing.

Time passed. I blogged. I felt occasional pangs of extreme guilt at the book I knew I should be writing that I wasn’t. At intervals, people whom I respect told me I should write it when I mentioned the idea.

Several years later, a person whom I think of as a friendly rival published a first book. I discovered a full page ad in full-color glory on the back of a Scientific American that had been sitting in my office for a while. You know those moments when your vision dissolves to red (or perhaps it’s green)? I had one of those moments. I spoke to a friend of mine who had published some books already about where to begin and my overwhelming terror of signing a book contract with a deadline when I wasn’t sure I could do it. He counseled: just start. Write the book you want to write. And when you reach the point where you really believe you can do it, go get it published.

That still wasn’t quite enough to kick my slothful hindquarters into gear, though. The enormity was still too enormous. Something more important always came up and I just couldn’t get started. I needed help. I had heard a RadioLab episode called “You vs. You” that said science has shown humans respond much better to avoiding short term pain than chasing distant gain. The opening story was about a woman named Zelda who had tried for years to quit smoking, and finally, in desperation, told her friend to donate an enormous sum of her money to the KKK if she ever picked up another cigarette. And it worked. I knew I was like Zelda. I needed the stick.

I discovered a website called stickk.com and created a commitment contract linked to an anti-science charity. I set a weekly writing goal of working on the book at least 15 minutes a day, five days a week, sick days and vacations excepted. I couldn’t stand the thought of giving my anti-charity ONE CENT of my money, so I only pledged $5 a week (the minimum). I could do anything I wanted in that 15 minutes, as long as it was related to the book. I found that the real obstacle was those first five minutes; once I’d made it past the five minute mark, I often worked much longer than 15 minutes. In the 75 weeks I worked that way, I only had to cough up the money once.

After 20,000 or so words, I got pregnant, had a baby, and then six months later the pandemic hit. That June, Scientific American’s blog network closed. My world imploded. There was a moment where I hit bottom. I vowed that once I got out of twin pandemic/baby prison, no fears of book writing would ever hold me back again. I was done being cowed and insecure. Then in December of 2021, we spent a night thinking our house had burned down in a massive wildfire. As we had been on holiday travel, my computer was in the house. And I couldn’t remember the last time I had backed it up. I thought that night the book was really dead.

Except it wasn’t. Though the fire came within a quarter mile of my house, it was spared. The miraculously saved book would wait no longer.

Then I got COVID from the person in whose house we’d sought refuge from the fire.

After I recovered, I opened up my files after three years of digital dust accumulation and was both dismayed and delighted by what I found. Some parts were a mess. But some parts sparkled. I worked every day from January to May to clean up and expand the book, ultimately amassing an additional 20,000 words. Now, NOW, I felt sure I could write this book, and that the material was worthy of it.

After my friend generously read the first half and offered comments, I went back to my agent with what I had. After a month, she decided to pass. That was tough to hear, but I knew I had only just begun to fight. The confidence I now felt was expansive and unshakable. I asked my friend if I should rewrite the opening of the sample chapter. We agreed I should. I tore it apart and started over. Then I went to a second agent who had approached me years ago.

If there is one lesson I have learned about the process of getting an agent, it is this: DO NOT go to just one agent at a time. Approach several. You’ll have to tailor your materials to each, but don’t just go to one, even if you think you have a strong preference. Because I have learned 1) what everyone says is true: after maybe just starting the damn thing, finding an agent is the hardest part of writing a book and 2) finding the right agent is a lot about finding an agent who both grasps your vision and knows the right editors to sell it to. Like many things in life, that’s a numbers game.

This second agent expressed interested, requested a phone chat, and asked an excellent and vital question about the engine of the book. I made a major structural adjustment that has remained with the book to this day. However, even with this major improvement, she, too, took a month to give me an answer, and the answer was no.

Now I was really getting my dander up. I knew, KNEW this book was meant to be. One final agent had approached me in the past, but by now I knew I wasn’t going to mess around with one at a time anymore. I had learned another good method was to read the acknowledgements in books similar to yours and find out the names of those authors’ agents. This time, I wrote to three. The results were: quick no, slow no, and quick yes. Yes! YEEEESSSSS! I finally got to yes. End Zone Dance, Nerd Style! [Gyrating around the office while singing “Levitating” along with Dua Lipa]

Now we had to sell the book to a publisher. Oh, and I had to write a proposal, as all I’d been working from so far was a giant sample chapter and a query letter. I was spooked about writing a 20-page proposal without getting their guidance first (says the woman who wrote 40,000 words before she had an agent or editor). As it turned out, I was left largely to my own devices and I used the book, Thinking Like Your Editor by Susan Rabiner and Alfred Fortunato. They gave sound advice. My agent was happy with what I turned in and requested few edits.

By January, we were ready to go. I was practically vibrating with excitement. He decided to start with just three editors. One bit within two days, and a second after a poke a few days later. The third, who had solicited a book from me directly before I had an agent, passed. You can never tell!

I ended up getting two interviews and two offers. I was a very happy lady. After all the self-doubt, dithering, work, and rejection (really not much by the standards of fiction writers), at last I had both the book and the means to bring it to you.

And so I shall. I promise you with every fiber of my being that this book will be in your hands in two years. And if I do my job right, it will be one of the most entertaining and interesting nonfiction books you have ever read. What I have already managed to dig out of those dusty library stacks — long forgotten science that maybe a handful of people on Earth ever read about even when it was published — will add up to a whole that I hope will delight and astound.

At the Oscars this year, Ke Huy Quan gave an acceptance speech that made me cry. He said, “Dreams are something you have to believe in.” Belief is an action — it’s something you have to do. If you’re scared, if you doubt your dream is possible, do what you need to do to make yourself believe you can do it. That made all the difference for me.

In the meantime, please continue enjoying this Substack, which I will update as often as I can when I need a break from slime molds. Next week: pitcher plants of Borneo with highly alternative ideas on fertilizer sourcing.

Until then, go outside this weekend, and spend some time noticing. You’ll be glad you did.

I was delighted to read about you and your book. I have been a fan of slime molds for most of my working life. I think I did a story on them for each publication I worked for. They are so cool, and your book title should be enough to sell the book in every marketplace.

I've always known that you were a winner.

This was a great read—grateful to discover it now, towards the two year mark! How’s the book going?